The Dolmetsch Story

by Brian Blood

The Dolmetsch Workshop is the most tangible aspect of a craft and music-making tradition stretching back to the 1880s when Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940), French-born but of Swiss origin, moved to London to begin a lifetime's study of early music and of the instruments for which it was written.

Possessing a remarkable range of skills, those of performer, maker, scholar and promoter, he was uniquely placed to understand the problems inherent in studying and re-presenting a tradition that, by the end of the nineteenth century, had completely disappeared, and where what little evidence there was, lay unrecognised in musical scores, treatises, tutor-books and in the qualified opinions of contemporary musicians, commentators and diarists, written in a bewildering array of styles and languages. Today, in the age of recordings, TV and films, radio, photocopiers, fax-machines and microfilm, we can barely comprehend the enormity of his task, but the world-wide interest and involvement of so many, both amateurs and professionals, in this rich and glorious field, owes much to his seminal work.

Dolmetsch received a thorough training as a craftsman at Maison Dolmetsch-Guillouard, 9 rue de la Prèfecture, Le Mans, France, his parent's piano, organ and harmonium manufactory. Graham Robb, in his book 'Discovery of France', quotes from a Larousse dictionary of 1872 which boasted that while lagging behind Britain and Germany in its heavy industry, France 'has no equal in all industries which demand elegance and grace and which are more concerned with art than manufacture'.

Dolmetsch escaped his responsibilities to the Dolmetsch-Guillouard business (which was renamed Gouge-Guillouard after Arnold's mother's remarriage) by marrying Marie Morel, a widow ten years his senior, before undergoing formal training in piano, violin and composition at the Conservatoire royal de Bruxelles where he first came in contact with musicians playing early musical instruments from the collection belonging to the Conservatoire. In 1883, he moved with his family to London, to enrol at the newly opened Royal College of Music, where he could further his interest in 'early music'.

It would be a mistake to think that an interest in early music was particularly remarkable in England at this time. J. A. (John Alexander) Fuller Maitland (1856-1936) described the situation at Cambridge, where he was a student in the 1870s, as follows: 'The professorial lectures which often admitted the existence of madrigals, virginal music, and such things, nearly always took it for granted that there was no beauty such as could appeal to modern ears, so that the respect with which we were encouraged to approach them was purely due to their antiquity.' In 1885, at the huge International Inventions Exhibition in The Albert Hall galleries, in South Kensington, London, A. J. Hipkins organised a display of and a series of concerts including instruments, some brought by Victor-Charles Mahillon from The Brussels Conservatoire. The Musical Times commented, 'some of the effects were beautiful as well as curious, while others were only curious.'

Appointed a part-time violin master at Dulwich College, but living in the London of the 1880s, he began to collect and later make viols, lutes and a range of early keyboard instruments, for his friends and for the many who flocked to concerts where they could hear him, his family and colleagues play newly discovered repertoire on treasured originals and on Dolmetsch's recent reconstructions. Harry Haskell ("The Early Music Revival - A History", pub. 1988, Thames and Hudson) writes: 'Owning a Dolmetsch instrument became a status symbol in smart society. Mrs Patrick Campbell ordered a set of psalteries to use in a performance of Das Rheingold, and Yeats purchased one for his friend Florence Farr to play while reciting his poetry.'

In 1894, actor-director William Poel founded the Elizabethan Stage Society.

William Poel (1852-1934) was the son of Professor William Pole (1814-1900), engineer, organist of St Mark's, North Audley Street, and author of Philosophy of Music (1879).

From an extensive study of a seventeenth-century theatrical practices, William Poel sought to recreate performances faithful to the intentions of their authors, particularly William Shakespeare, recovering the proper poetic metre and pace intended by returned to the original texts, and presenting them in a more natural setting.

The Elizabethan Stage Society acted on a recreated Elizabethan stage for their productions of plays from the period, complete with music performed by members of the Dolmetsch family. The picture below, taken in about 1895, shows Arnold Dolmetsch (lute), Elodie Dolmetsch (standing) and Hélène Dolmetsch (bass viol). Dolmetsch superintended the music for all the Society's revivals until 1905. George Bernard Shaw drew up a critical balance sheet of the Society's achievements to date.

Poel, he said, had unquestionably made a contribution to theatrical art . . . the truth is that nothing like the dressing of his productions has been seen by the present generation: our ordinary managers have simply been patronising the conventional costumier's business in a very expensive way, whilst Mr. Poel has achieved artistic originality, beauty, and novelty of effect, as well as the fullest attainable measure of historical conviction. Further, he has gained the assistance of Mr. Dolmetsch, and so brought the most remarkable musical revival of our time to bear on his enterprise. . . . He has done extraordinary things with the amateur talent at his disposal, the last few performances showing not only that he has at last succeeded in forming a company of very considerable promise, but that something like a tradition of Elizabethan playing is beginning to form itself in the Society. (taken from: The Saturday Review (16 April 1898); reprinted in Our Theatres in the Nineties (1932) Vol. III) |

These remarkable productions were to influence how people staged Shakespeare in the first half of the twentieth century (today the Globe Theatre in London continues the ESS tradition), a great change from the bizarre archeologically accurate realistic-romantic productions with their emphasis on set design. Poel was concerned to concentrate on the actor and on the text and on or about 7 February 1897, William Poel produced Twelfth Night at the Hall of the Middle Temple, where the play had been performed in 1601. The distinguished audience included the Prince of Wales, sitting as a Bencher of the Inn, Princess Louise and the Duke of Teck. Arnold Dolmetsch, his wife Elodie and his daughter Hélène performed suitably selected period music for the production.

Dolmetsch's daughter Hélène (seen above in 1922 when she was 44, with her Bergonzi viola da gamba) began performing in public when she was about 12 years old. The London correspondent of the Otago Witness, in an article published 6th December 1896, makes mention of her playing, describing her as a young woman of 16 (she was probably 17).

In 1897 Hans Richter (18431916) engaged Dolmetsch to play recitatives on his harpsichord in Don Giovanni at Covent Garden. His 'Beethoven' pianos, in particular, were among the many beautiful instruments made during his sojourn in London in the late 1890s.

Among a wide circle of influential friends including the central figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement (led by William Morris (1834-1896), see also The William Morris Gallery, and William Morris in the US, and including Selwyn Image (1849-1930), Helen Coombe (1864-1937), Herbert Horne (1864-1916) and Roger Fry (1866-1934) whose designs featured on a number of Dolmetsch instruments) and an army of admirers (including Gabriele d'Annunzio (1863-1938) (poet), whom Dolmetsch first met in Rome in 1897 and who was to be a frequent companion in long walks around the family home in Fontenay-sous-Bois when Dolmetsch was working for Gaveau), and George Bernard Shaw (18561950) who has left us vivid and appreciative reviews of Dolmetsch's London concerts.

for some time past Mr Arnold Dolmetsch has been bringing the old instrumental music to actual performance under conditions as closely as possible resembling those contemplated by the composers. Here [at Mr. Dolmetsch's house in Dulwich] the music, completely free from all operatic aims, ought, one might have supposed, to have sounded quaintly archaic. But not a bit of it. It made operatic music sound positively wizened in comparison. Its richness of detail, especially in the beauty and interest of the harmony, made one think of modern English music of The Bohemian-Girl school as one thinks of a jerry-built suburban square after walking through a medieval quadrangle at Oxford. If I had a good orchestra and choir at my disposal, I would give a concert of Purcell's Yorkshire Feast and the last act of Die Meistersinger. Then the public could judge whether Purcell was a really great composer or not, as some people, including myself, assert he was. Mr. Dolmetsch has taken up an altogether un-English position in this matter. He says, "Purcell was a great composer: let us perform some of his works." The English musicians say, "Purcell was a great composer: let us go and do Mendelssohn's Elijah over again and make the Lord Lieutenant of the county chairman of the committee." |

Ezra Pound (1885-1972) immortalised him in Canto LXXXI, and George Moore (1852-1933) (sometimes called the Irish Balzac) based an entire novel, Evelyn Innes, around Dolmetsch's work, his daughter Hélène, their Dulwich home and early instruments. W.B. Yeats (1865-1939) turned to Dolmetsch for advice on a suitable instrument to accompany the 'chaunting of verse' while James Joyce (1882-1941), announcing that he planned to 'coast the South of England from Falmouth to Margate singing old English songs' to his Dolmetsch lute, used a futile attempt to purchase such an instrument from Dolmetsch as the inspiration for a similar transaction contemplated in Ulysses. For Percy Grainger (1882-1961) Dolmetsch was a fertile source of the early English music that so inspired him, and F.T. Arnold, the musical scholar, turned frequently to Arnold Dolmetsch for advice when writing The Art of Accompaniment from a Through-Bass as practised in the 17th and 18th centuries, long recognised as the standard authority). He enjoyed great success as a promoter of English music of the 16th and 17th centuries. Margaret Campbell, his biographer, comments that 'standing barely five feet tall, and dressed in a velvet suit, complete with knee britches, lace ruffles and shiny shoe-buckles, his appearance made him look more pre-Raphaelite than the pre-Raphaelites themselves'.

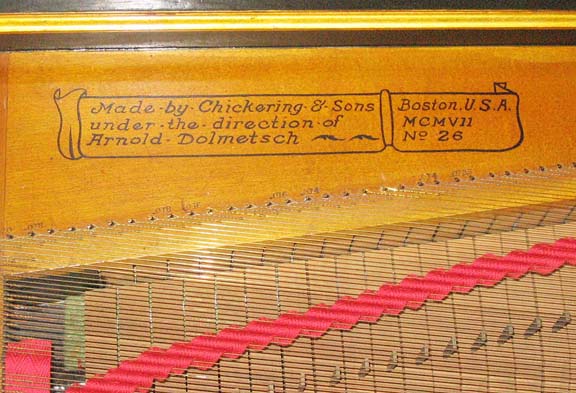

His fame spread abroad as well as throughout England, leading him to be invited to the Chickering Factory as director of a special department at the piano factory making harpsichords, clavichords, and other instruments on Tremont Street in Boston, Massachusetts (between 1905 and 1910), and later in the Gaveau Workshops in Paris.

During these periods in America and France some of his very finest instruments, now treasured heirlooms, were produced. (examples are to be found at The American Piano Museum, The Bate Collection, Oxford and the Russell Collection, Edinburgh).

Of interest too, is the Cambridge, Mass. house that Arnold Dolmetsch commissioned from the architects Luquer and Godfrey but incorporating designs produced by Dolmetsch himself. Certain features of the house (completed in 1908 and originally given the address 11 Elmwood Avenue,the house was later readdressed as 192 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Mass.) are protected by a codicil in the deeds, inserted by Simon Marks, who purchased the house from Arnold Dolmetsch in 1911. The house would become for a time the home of Felix Frankfurter (18821965) who was to be appointed an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. (a second photograph of 192 Brattle Street).

A fascinating view of the late Victorian London concerts organised by Dolmetsch comes from Jessica Douglas-Home's biography of her great-aunt, Violet, the exotic harpsichordist and clavichordist Violet Gordon Woodhouse. One concert in particular, caught the imagination of the American harpsichordist Maggie Cole who with a group of friends, including the harpsichordists Malcolm Proud and Alistair Ross, gave a concert at the Wigmore Hall, London on the evening of 14th December 1999 in celebration of the instrument's renaissance during the hundred years following a performance of Bach's Triple Harpsichord Concerto in C at 6 Upper Brook Street, London W1, on 14th December 1899. Upper Brook Street lies just across Oxford Street from the Wigmore Hall but the building that stands at the address is newer. To the north, over the road, lies the facade of the American Embassy.

The original program was given under the direction of Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch.

PROGRAMME - 14th December 1899 PART 1 1. Suite No. 1 in D minor for Four Viols by Matthew Locke, 1670. 2. Chacone for the Harpsichord, G. F. Handel, 1721. 3. A Song from the Opera of "Sosarmes", accompanied by Violins and Harpsichord. G. F. Handel 4. Sonata for the Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord obbligati, accompanied by a Second Harpsichord. Georg Teleman, c. 1730 INTERVAL PART II 5. Sonata for the Harpsichord, being No. 9 in D major: W. A. Mozart 6. Song, accompanied by the Harpsichord. W. A. Mozart 7. Sonata No. 3, for the Harpsichord and Viola da Gamba. J. S. Bach 8. Concerto in C major for Three Harpsichords, Two Violins, Viola, Violoncello and Violone. J. S. Bach The Names of the Performers The Consort Viols : The Violins: Mr. W. A. Boxall, Mr. H. M. Matheson. Tickets, 10s 6d. to be had from Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch, |

Jessica Douglas-Home writes: 'Although this was to be a public concert, Violet prepared as if for a private occasion. A small library, planned as [her husband] Gordon's smoking-room, led off her drawing-room. By letting down a thick green velvet curtain in front of the archway, Violet turned the library into a retiring chamber, from which the Dolmetsch family emerged in Elizabethan costume onto a raised dais where the harpsichords stood. There being no electricity in the house, the drawing-room was lit by two statues holding oil lamps in the niches on either side of the double doors, and by violet-coloured wax candles set on the green-striped walls in flat brass scounces. Since no paintings could compete with the beautiful ceiling, Violet had hung the room with silhouettes on glass and engravings in low tones of brown, grey and black. The dark, polished boards of the uncarpeted floor gleamed in the candlelight, and high piles of cushions haphazardly filled the window seats.

During the day Gordon had arranged the flowers - ferns, roses and lilies - brought up from the hothouses at Wootton. The guests were invited for half-past seven, an hour before the concert, and were offered cheese croutons, sandwiches, ice creams and white wine, the idea, not altogether successful, being to avoid an unseemly rush for the buffet. Violet's room could seat fifty and the audience was allowed to overflow on the landing and the staircase.'

Maggie Cole observes, 'questions of presentation like venue and acoustic, costume and image, remain current concerns: what's the best way to restore a musical 'old master' to enhance present experience? The 'historically informed' approach brings no absolutes with it, and throws everything in our conventional concert and opera life up for discussion too.' This description of the Brook Street concert echoes that written by Mabel Dolmetsch of a house concert given by the Dolmetsches in their family home, 'Dowlands', at 172 Rosendale Road in Dulwich, a few years earlier.

The concert room, tinted a soft diaphanous green, was entirely illuminated by wax candles, set round the walls in hand-beaten brass sconces, and interspersed with rare lutes and viols, suspended from hooks.... There was a pleasantly informal atmosphere at these concerts; and the interludes, during which excellent coffee and petit fours were handed round, enabled one to appreciate the unusual nature of the audience.' |

The approach of the German army towards Paris during the First World War forced the family back to London but under threat from the bombing by Zepplins, the Dolmetsch family decamped to the verdant beauty of Haslemere in Surrey from whence countless millions of early instruments have flowed. The family moved into Jesses, which remains the main family home, in December 1917. Haslemere (for more click here) has a special place in recorder history - it was there, in 1920, that Arnold Dolmetsch completed one of the first, and certainly the most influential, twentieth-century recorder, based on one of his originals (an alto by Bressan, now part of the Dolmetsch Collection housed at the Horniman Museum, Forest Hill, London). The antique instrument had, by that time, been mislaid on Waterloo rail station (April 1919), left behind in the rush to catch a train back to Haslemere after a concert by the family at the Art Worker's Hall. This loss was the spur for one of the most remarkable acts in the recorder's revival. Arnold Dolmetsch, now over sixty years old, worked for many months to uncover the recorder's secrets before producing a working model. Over the following six years he completed the main consort of recorders (descant, treble, tenor and bass) all at low pitch and based on historical originals. This consort featured in the 1926 Haslemere Festival of Early Music. Peter Harlan, visiting an early Festival, purchased a set of recorders from Dolmetsch and, despite being confused by their being at low pitch, commissioned derivatives from German manufacturers and so started the mass recorder movement in Germany (for further details visit The Recorder Homepage).....and what of the lost recorder? It was purchased at a junk shop and returned to its rightful owner.

Outside his immediate family circle, Dolmetsch had many pupils (makers, performers and scholars). Among many others these included Gunter Hellwig (viol maker), John Challis (harpsichord maker), Elizabeth Brown (harpsichordist, who married Robert Goble (1903-1991), craftsman from 1924 to 1937 in the Dolmetsch workshops, later owner of his own harpsichord-making business, Robert Goble and Son), Miles Tomalin (music teacher, composer, communist poet and veteran of the Spanish Civil War), Diana Poulton (lutenist and cataloguer of the music of John Dowland), Dorothy Swainson (harpsichordist), Dr. Llewelyn Wyn Griffith (1890-1977) (novelist, poet and translator, who studied 16th and 17th century viol music under Dolmetsch and founded the Early Welsh Music Society to interpret, perform and record early Welsh harp music in the British Museum manuscripts), Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911-1984) musicologist/harpsichordist and Robert Donington (musicologist and secretary of the Dolmetsch Foundation) who wrote that he and others have not so much improved on Dolmetsch's basic work as extended it in a way that Dolmetsch would have done, had he lived.

Ralph Kirkpatrick recorded Bach on a 1908 Dolmetsch double manual concert harpsichord. See here for more information on the recording.

In 1937, Miles Tomalin went to fight in the Spanish Civil War as a member of the International Brigades. He inscribed the names of the battles in which he fought on his Dolmetsch recorder. (ref. Imperial War Museum - Spanish Civil War exhibition)

| Dolmetsch's third wife, Mabel, was a scholar in her own right publishing seminal books on early dance. She too had remarkable pupils including Polish-born Myriam Rambert who later became one of the principal architects of English ballet as Dame Marie Rambert. For an example of her influence go to here. |

The Interpretation of the Music of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries by Arnold Dolmetsch (1915) (reprint including Appendix of Musical Examples available from The Dolmetsch Workshops) was the result of his research and experience. Dolmetsch's formidable powers as a scholar continued to the very end of his life, although as a player ill-health and age took their inevitable toll. Those who have heard the clavichord recordings he made of Bach's 48 preludes and fugues, will appreciate that one listens more to the message than to the messenger. His tricky personality gave him a reputation for being a hard, even a difficult task master. What might start out in hope could end in tears.

Suzanne Bloch wrote to Arnold Dolmetsch, who had begun playing the lute in the late 1880s, on 25th May 1934.

Dear master,

.... Of course I shall play in your concerts. I shall do everything, dance, sing, play the harp, the lute! And I shall smile....

The world is in chaos: uncivilized at the present time. People need music and instruments like yours which bring peace and courtesy...

I will come to you as a humble disciple to work hard and try to become a real lute player, not a drawing-room amateur...Your example is a very great inspiration to me and I hope to become worthy of you.

Your devoted,

Suzanne

Contrast this with her article "Saga of a Twentieth-Century Lute Pioneer", published in the Journal of the Lute Society of America, Vol. II (1969), pp. 37-43.

At this time my salvation came, in the person of Diana Poulton. I had heard about this "other lute player" who had studied with Dolmetsch for about three years but so far had not played at the festivals as a soloist. I was curious and a bit apprehensive, for in those early days we each felt that we were the "only one" truly to revive the lute. But when we met, we had an immediate rapport. At once she righted me about lessons with Dolmetsch, saying that for three years he had kept her on "All of Green Willow" and at times had made her weep. She and her husband Tom had done their own research in London, and Diana had inherited a sheaf of lute tablatures copied by Peter Warlock. They lived in Heyshott in a wonderful little thatched-roof cottage with a garden full of herbs and flowers and a tame magpie named Jack. Diana kept goats that she milked and she made her own cheese. This extraordinary down-to-earth way of living made a great impression on me. it was like a dream, away from the materialistic way of life that threatened to get worse and worse. After a meal, Diana would play her lute, reading fluently from all sorts of tablatures, or accompany Tom who sang in an extremely musical way. At last I heard the lute as it should sound.

As I advanced in my playing, Diana told me of the wonderful duets in "Jane Pickering's lute book." She had some of them copied, and one good day for the first time in probably three centuries, they came to life in the little cottage in Heyshott.

We then began to work seriously on some of the duets and played a set of them in an informal performance at the Haslemere Festival, to the delight of everyone and the high praise of Rudolph Dolmetsch, the oldest and most gifted musician of the Dolmetsch family. Our performance had not been known of by Arnold Dolmetsch, who would have vetoed our playing. Rudolph then insisted that we play at the following Haslemere Festival in 1935.

That winter I had many chances to play the lute. My real debut was, of all places, in Carnegie Hall to illustrate the instrument in Ernest Schelling's children's concerts. I was skeptical of an audience being able to hear a lute in so large an auditorium, so Schelling plunked me on the stage, told me to play, and ran to all the different parts of the hall, even upstairs, while I played my "safest" pieces. Every so often I would yell, "Vous m'entendez, Monsieur Schelling?" to which he would shout, "Mais bien sur."

I already sensed, however, that this instrument had qualities that were not for a huge hall such as Carnegie. By then the lute had begun to represent something of great spirituality to me. At first I was not aware of it; I just wanted to play. Now, however, I can see that the young generation of today feels what I felt so many years ago--that same reaching out for a subtlety, a purity, a simplicity, a delicacy, and a rhythmic vitality. I felt so rich when I could play a short piece perfectly. To own a treasure is to be able to do justice to a piece of lute music. I discovered something else when I joined Carl Dolmetsch on a short American tour. I had to learn the virginals in three days and also play the recorder, but the real thing was to test myself as a lute soloist. Then I discovered the miracle of playing a simple piece well on the lute, of feeling the magic created by the sound of the instrument--this wondrous hush, a spell on the audience. It was as if suddenly the breath of the past were upon us all, making us forget the noises, the tensions of our times.

The next summer when Diana and I began to rehearse the lute duets we were to play at the Festival, we decided to work especially hard and show what the lute really could do. Arnold Dolmetsch had capitulated by then to Rudolph's and Carl's demands that we play the duets. Not to be outdone, he decided to do the four-lute pieces of Nicolas Vallet, and he would play the most difficult part, the treble, on a little lute that he had constructed for the occasion.

Oh; those rehearsals for the four lutes! Dolmetsch had great difficulty with the runs in the Vallet; after all, the man was eighty-two years old, and it was remarkable that he could play as well as he did. He insisted on the use of gut strings, so we would go over yards of surgical gut, flicking a length the way Mersenne advises to make sure the string would not be false. At rehearsals on those hot July days, Dolmetsch would have us all tune separately, listening to us and directing us--much to my disgust, as I knew we could all tune perfectly well. By the time all four had tuned (4 x 19 strings!!), somebody's treble would "pop," and we would have to start all over again. One day, exasperated with the breaking of the strings, I went to London and bought several trebles at the shop of a stringmaker who made silk lute strings. At the next rehearsal, Dolmetsch began to express surprise that my treble stood so well. He had been violently against the use of silk strings, but he was not to be outdone. That night he stayed up, constructing a winding machine for making silk strings, insisting his strings would be better than those I had bought. The next day he came with a string and gave it to Diana, who was obliged to use it, and since it was not as strong as the others it also went "pop"--and so it went.

The day of the concert when we were to play the duets, Diana and I were very nervous for we had chosen some difficult duets and had worked hard to bring out subtleties of rhythmic expression and some lovely coloring in the "Spanish Pavan." We walked onto the stage, set our music on the stands, checked our tuning, and were ready to start when a voice came from the front row, "Lower your music stands so we can see you." This was Dolmetsch, timing his comment perfectly. Diana and I lowered our stands, looked at each other sending a mutual message, "He won't shake us; no, he won't." The duets went off as well as we had hoped. The next day when Gerald Hayes wrote in his review, "At last the lute was given due justice at the Haslemere Festival," we felt that we had accomplished our goal. From then on, Dolmetsch gave in and allowed others to play lute at the festival. I felt a bit sorry for him that day--he looked beaten--but Diana said, "I am not a bit sorry; after all, he made me cry for three years."

This is not a success story--just the beginning of the long, wondrous, hard road that can never end for any lutenist. Some have gone way beyond what Diana and I have done. But in those early years there was a great magic in pioneering that sometimes I feel has been lost with the recent commercialized interest in the lute, for which playing fast and loud seems to be the one criterion. Yet, there are still so many young people who seem to be searching as I did so many years ago for this subtle beauty that is beyond all things to enrich our spirits. A minute of beauty can be a complete universe.

Many years later, Diana Poulton remembered her own first meeting with Dolmetsch.

While I was a student at the Slade School of Art my Mother took me to one of Arnold Dolmetsch's concerts at the Hall of the Art Worker's Guild in London. This changed the whole course of my life. I decided I wanted to learn to play the lute and, after I was married, I was able to ask Arnold Dolmetsch to make one for me. I used this beautiful instrument for the whole of my performing life.

Dolmetsch's collection, those instruments that he owned at the time of his death, was acquired from the Dolmetsch family by The Horniman Museum, based in south London. Those interested in seeing the Dolmetsch Collection of Early Music Instruments should contact the Museum itself. Click here for more information about the Horniman Museum's collections.

Invariably, Dolmetsch's first instinct was to copy original models, (see Ralph Kirkpatrick's comments), but after a lifetime in the field it was no wonder that sometimes he sought to 'improve' on the original masters, applying the lessons they had learned, or maybe perfecting ideas they had tried unsuccessfully to introduce, making use of new materials or creating new designs to meet present day needs. He argued that instrument making had always been, and should continue to be, an ongoing process of development where each design reflected the particular skills and tastes of the maker rather than just a reaction to the more restricted requirements of composers or performers from the past or present. The 'craft' of instrument-making should be more than just 'reproduction', in the same way that ornamentation in music should be more than playing only what early masters had committed to print. Dolmetsch believed that all the 'lost' instruments of antiquity had a rightful place in modern life if only latter-day craftsmen would learn again to make them and performers learn again to play them sympathetically. His friends in the Arts and Crafts movement had brought mediaeval design back into fashion not to have us live in the past but to have the past inspire the present. If a process akin to natural selection had consigned early music and early musical instruments to extinction, Dolmetsch was determined to reverse it. To apply an analogy, he was doing what modern-day scientists still only dream of - taking remnants of DNA from dinosaur fossils and bringing those long-departed creatures back to life to live, not in a recreation of their prehistoric past, but in the present.

How did Dolmetsch and his work appear to his contemporaries?

It was Dolmetsch, the Belgian [sic] musician, who first taught me what a great musician Sullivan really was; till then I knew nothing of him except as a writer of the comic operas; but Dolmetsch taught me the splendor of 'The Golden Legend' and the beauty of some of his songs, such as 'Oh Mistress Mine' and 'Orpheus with His Lute'. Dolmetsch explained many musical problems to me. Of course, everyone knows that he was the first to make the harpsichord and clavichord as in the earlier days, but to hear him play Bach on the instrument that Bach had written his music for was an unforgettable experience: it was like hearing a great sonnet of Shakespeare perfectly recited for the first time.

extract from, "My Life and Loves" (1925), by Frank Harris

"I have seen the god Pan." "Nonsense." I have seen the God Pan and it was in this manner: I heard a bewildering and pervasive music moving from precision to precision within itself. Then I heard a different music, hollow and laughing. Then I looked up and saw two eyes like the eyes of a wood-creature peering at me over a brown tube of wood. Then someone said: Yes, once I was playing a fiddle in the forest and I walked into a wasp's nest ....

When a man is able, by a pattern of notes or by an arrangement of planes or colours, to throw us back into the age of truth, a certain few of us - no, I am wrong, everyone who has been cast back into the age of truth for one instant - gives honour to the spell which has worked, to the witch-work or the art-work, or whatever you like to call it. Therefore I say, and stick to it, I saw and heard the God Pan; shortly afterwards I saw and heard Mr. Dolmetsch.

extract from, Affirmations, part of Ezra Pound's "Literary Essays 1915".

A first-rate clavichord from the hands of an artist-craftsman who, always learning something, makes no two instruments exactly alike, and turns out each as an individual work of art, marked with his name and stamped with his style, can be made and sold for £40 or less, the price of a fourth-rate piano (no. 5768 from Messrs. So-and-so's factory) which you can hardly sell for £15 the day after you have bought it. Above all, you can play Bach's two famous sets of fugues and preludes, not to mention the rest of a great mass of beautiful old music, on your clavichord, which you cannot do without a great alteration of character and loss of charm on the piano.

These observations have been provoked by the startlingly successful result of an experiment made by the students of the Royal College of Music. They, having their ears and minds opened by Mr. Dolmetsch's demonstration, to the beauty of our old instruments and our old music, took the very practical step of asking him to make them a clavichord. It was rather a strange request to a collector and connoisseur; but Mr. Dolmetsch, in the spirit of the Irishman who was invited to play the fiddle, had a try; and after some months work he actually turned out a little masterpiece, excellent as a musical instrument and pleasant to look at, which seems to me likely to begin such a revolution in domestic instruments as William Morris's work made in domestic furniture and decoration, or Philip Webb's in domestic architecture. I therefore estimate the birth of this little clavichord as, on a modern computation, about forty thousand times as important as the Handel Festival.

George Bernard Shaw, writing in "World", 4th July 1894.

The work you are doing is so deeply beneficial to the cause of music - and, indeed, to the betterment of mankind - that it ought to be blazoned forth as widely as possible...

Your concerts are the most liberal musical education I have ever witnessed. Also they are the most enjoyable concerts I have ever heard....

I am, in music, a modernist... But I realize that true art has no oldness or newness, that all periods of human life produce great art, and that artistic culture depends upon a knowledge of the past, an understanding and love of the past...

The Fantasies for Viols, as you do them, are a far more subtle and exalted form of string music than any of the usual 'quartets' that are everlastingly heard....

It seems to me that some means should be taken to make a world public realize that the old music on the old instruments (made available and practical by you) is a necessary part of musical study (alongside the study of Beethoven, Bach, Wagner, etc.), and that it can be studied, as living music, from you!

Percy Grainger, extracts from letters written to Arnold Dolmetsch.

Jessica Douglas-Home talked about Violet Gordon-Woodhouse's relationship with Arnold Dolmetsch: "My father told me that Violet took a few lessons with Dolmetsch on the harpsichord in the mid-1890s. She bought a 1785 Thomas Culliford harpsichord from him (which he adapted for her) in 1899 ..."

When Dolmetsch returned from America in 1910 after an absence of several years, he and Violet resumed their friendship and gave a number of performances together, including one with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1915. When Dolmetsch's book (The Interpretation of the Music of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries) was published in 1915 he gave Violet an advance copy with a fulsome dedication. After hearing a concert of Dolmetsch's own compositions at his eightieth birthday celebration in 1938, she wrote to him.

"I never expected to hear such music, and I was touched and moved to the heart, and I AM NOT EASILY STIRRED. I felt exhalted."

Richard Troeger's interview with Jessica Douglas-Home (VGW's great niece) published in April 1997 in Continuo

| In 1925, Arnold Dolmetsch passed the direction of recorder production over to his younger son, Carl (see left). His older son, Rudolph, had married and moved to London where he was gaining a reputation both as a conductor and a composer. His sad loss, when his ship was torpedoed at sea in December 1942, robbed the family and music in general of a rare talent. (on the right: Rudolph at the harpsichord, Nathalie on tenor viol, Carl on recorder and Millicent, Rudolph's wife, on bass viol taken in 1936) |  |

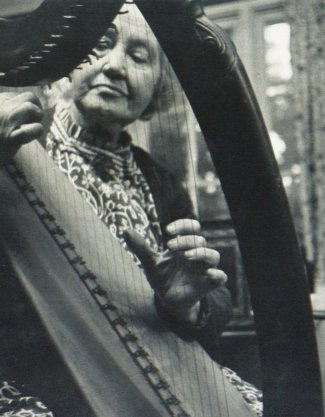

In the 1930s Arnold Dolmetsch, working in Haslemere, became interested in the medieval Welsh harp music preserved in Robert ap Huw's seventeenth century manuscript. Dolmetsch worked on the tablature and produced "translations" into staff notation. He also made some harps based on the surviving Irish and Scottish instruments. Although he was the first to apply historical methods to the making of early Gaelic harps, he nonetheless applied contemporary Celtic harp principles to the designs, presumably assuming that they preserved ancient traditions. Some of his harps were strung with gut and some with wire. His wife, Mabel Dolmetsch, recorded a selection of the pieces using reconstructed fingernail techniques in 1937. [this information taken verbatim from : http://www.earlygaelicharp.info/history/early20th.htm]

In the 1930s Carl Dolmetsch completed the upper end of the family with the sopranino as well as producing recorders at modern pitch - until then all production had been at low pitch. Production at low and modern pitch continued side by side until, on the retirement of the remaining family members, the factory closed in March 2010. Until then the company had continued making many kinds of hand-made early musical instruments (viols, lutes, harps, rebecs, harpsichords, spinets, clavichords, recorders, pipes and tabors, tambourin, psalteries, and so on). A delightful, though not wholly uncritical, description of the Dolmetsch workshop (as it was in 1947) is given by Frank Hubbard who, in that year, joined the firm as an apprentice.

The first Dolmetsch plastic recorders were manufactured in 1947, establishing the name in the area of educational musical instrument manufacture. More recently the family has formed manufacturing and design associations with other manufacturers including Coolsma in Holland - owned by Aafab b.v. - who continue to produce plastic and mid-priced Dolmetsch recorders. Members of the family (Jeanne Dolmetsch, Marguerite Dolmetsch and Brian Blood) continue teaching and playing as well as editing recorder music.

There can be very few corners of the earth where the recorder is not made or played. Nicholas Lander's The Recorder Homepage is now the vade mecum for all net-connected recorder enthusiasts.

references:-

- Dolmetsch: the man and his work by Margaret Campbell published by Hamish Hamilton (1975)

- Personal Recollections of Arnold Dolmetsch by Mabel Dolmetsch (reprint available from The Dolmetsch Workshops)

- The Interpretation of the Music of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries by Arnold Dolmetsch (1915) (reprint including Appendix of Musical Examples available from The Dolmetsch Workshops)

- The Early Music Revival - A History by Harry Haskell published by Thames and Hudson (1988)

- Carl Dolmetsch - Obituary

- Carl Dolmetsch - Obituary on the web site of the UK Society of Recorder Players

- Carl Dolmetsch - An Appreciation by Ian White of the Viola d'Amore Society

There are further references listed at the bottom of our dolmetsch history page.